It’s not rock and roll I know, but I do like it. It, in this case, is the story of Zoe Gail, who died on 20 February 2020. She was born on 20 February 1920, so she died on her actual 100th birthday. Only the Daily Telegraph published her obituary and I’ll confess that I had never heard of her, but it was such an amazing story I thought I’d make a note for an annual round-up of those we lost in 2020 for BBC Radio London.

Zoe Gail was a musical comedy star during and just after the Second World War. She was actually from South Africa, born Zoe Stapleton in 1920, but at 17 was already a striking beauty with long red tresses and a delightful singing voice, so her pushy showbiz mother sent her to London to be a star. Almost immediately she was snapped up to sing at the Comedy Theatre in Panton Street, in between the scene changes in revue shows (it was common that a singer would come out for 5 or 6 minutes to keep the audience entertained while they moved scenery and furniture around).

She was such an immediate hit that the management of the Comedy Theatre put her on a substantial contract. Throughout the war she became a bigger and bigger star and top West End attraction at such places as the Hippodrome and the Palladium.

It’s odd to think that despite wartime, austerity and blackouts, the West End sort of continued. London was actually under a blackout from 1 September 1939, two days before war was declared. In those early days, even lighting a match in the blackout could result in a fine, but later a more realistic approach was adopted, with limited use of illuminated signs and what was called ‘glimmer’ or ‘star’ lighting. All lights however had to be extinguished during air raids, though from September 1944 onwards, the regulations were relaxed to allow a ‘dim-out’, which meant lighting could be in effect the equivalent of that night’s moonlight

As war broke out, a large number of West end theatres did close because let’s face it, we were all expecting a pretty immediate German bombing campaign and wanted to keep our citizens safe. However, when those bombings failed to materialise, many theatres re-opened within weeks but were not allowed to use bright lights in the way we might typically think of in, say, Piccadilly Circus.

London theatre was an important part of life for the British people during World War II. As the war progressed, rules were gradually relaxed, especially when it became clear that the continuation of normal leisure facilities would be essential to maintain general morale and some sense of normality. Theatres became an important escape for the Londoners, a reprieve from their problems and theatre-going was a popular pastime. That’s not to say there weren’t difficulties: staff were obviously called up, costumes and make up were rationed, in fact performances moved earlier in the day, to lunchtimes and matinees, so that they took place before blackout at nightfall, depending on the time of the year.

Air raids did still disrupt performances. The programme always included instructions on what to do in the case of an air raid (run like hell to Piccadilly Circus underground station, I’d suggest). Audiences were warned when an air raid was in progress via illuminated signs and were free to leave for a shelter if they wished. ‘All we ask’ said the programme ‘is that if you feel you must go, you will depart quietly and without excitement’. Many theatregoers preferred to stay put and enjoy the play.

Things obviously got much easier once the Blitz was over, but the Doodlebugs and V2 flying bombs of 1944 brought another crisis, closing many shows. However, the shows that stayed open just mopped up all the folks who would have gone to the ones that closed, so everyone did rather well out of it. It’s worth saying that troops on leave were a huge part of the audiences too. By April 1945, the German war-making capability had been badly damaged and was nowhere near as dangerous as it had been, so street lighting was switched on in April 1945; on 30 April, the day Hitler committed suicide, Big Ben was lit 5 years and 123 days after the Blackout was first imposed. Whilst streets could be lit, there were supply issues so there was some degree of rationing of power. The bright lights of West End theatres and the advertising boards of Piccadilly Circus were not considered crucial, so the West End remained in dim out mode till – would you believe – April 1949, almost 10 years after they were switched off.

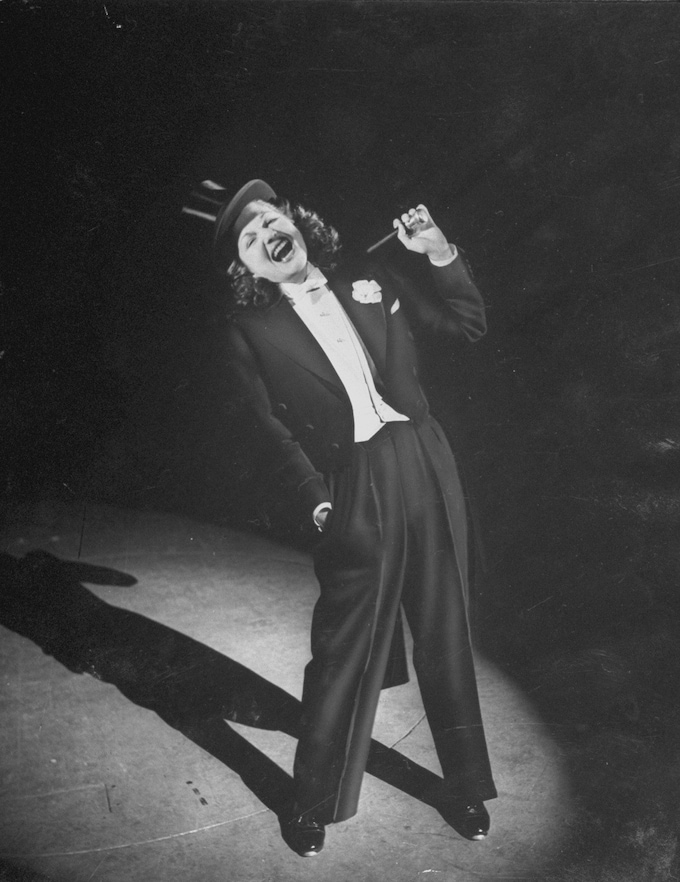

Anyway back to Ms Gail. She was one of the West End’s biggest stars all through the war on the stage and in the movies too. She was however quite controversial. She often dressed slightly androgynously in a man’s dinner suit when on stage and some of the lyrics in her revue Strike a New Note at the Prince of Wales Theatre were a bit racy for the time. Her big song was I’m Going to Get Lit Up When the Lights Go Up in London, whose lyrics included such filth as:

I’m going to get lit up when the lights go up in London;

I’m going to get lit up as I’ve never been before

You will find me on the tiles, you will find me wreathed in smiles;

I’m going to get so lit up, I’ll be visible for miles!

The critics were aghast at such louche behaviour. One disapproved of her male tuxedo costume, calling it ‘strange, hermaphroditic garb’ and denounced the spectacle of a young and beautiful woman appearing on stage vowing to get “pickled and positively pie-eyed” when the blackout ended. Her biggest fan, however, was Winston Churchill who just happened to be Prime Minister and after seeing the show he promised her that when the lights came back on in the West End, she would be the lady to switch them on. And despite the fact that Churchill was voted out of office almost the moment the war ended, strings were pulled and his promise was kept.

So, on 2 April 1949, Zoe Gail climbed out on to the balcony of the Criterion Restaurant overlooking Piccadilly Circus. Dressed in top hat, tie and tails, standing in a spotlight she sang I’m Going to Get Lit Up When the Lights Go Up in London to a huge crowd of over 10,000 packed into Piccadilly Circus below. Then, with an Abracadabra and a Hey presto!, she flicked a switch and the Bovril sign came on first followed by the rest of the lights in Piccadilly Circus. As a final flourish, she tossed her top hat into the crowd and opened a jeroboam of champagne.

She went from strength to strength after the war, on the stage, nightclubs, radio, TV and the movies. She appeared at the 1952 Royal Variety Performance in November 1952, the first of the Queen’s reign where she received a standing ovation when she sang Burlington Bertie in her trademark male tuxedo. She moved to Las Vegas in 1958 and appeared in cabaret in cabaret for several years. When she left show business, she ran a jewellery shop and bought and sold houses, but lost all her money in a scam and she died aged 100 penniless and sharing a room in an old people’s home. Nevertheless, as late as in her nineties, she would always get meticulously groomed for visitors, still maintaining that the night she switched on the lights in Piccadilly was the greatest moment of her life.