It’s April Fool’s Week as I write and whilst I may be a couple of days late but I thought a quick round-up of the Greatest Rock and Roll Hoaxes might be in order. A mixture of conspiracy theories, cheeky scams, hilarious pranks and downright evil sleight of hand.

The Sonny Boy Williamsons

The earliest hoax of the rock and roll age is the story of Sonny Boy Williamson. Or to be strictly accurate Sonny Boy Williamsons. Older Bluesheads out there, veterans of the Crawdaddy back in ’63, will remember kneeling at the feet of the revered blues pioneer, guitarist, singer and harmonica player when he toured here with The Animals and The Yardbirds – whose guitarist was an 18-year old Eric Clapton.

Only one problem. Sonny Boy Williamson died in 1948.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5369804-1391717398-1977.jpeg.jpg)

The original Sonny Boy – John Lee Williamson from Tennessee – was the best-known blues man in the USA during and just after the war. He had made his way to Chicago in the early 1930s, started recording in 1937 and made a number of songs which are regarded as blues standards, not least Sugar Mama Bluesand Good Morning Schoolgirl, which was Rod Stewart’s first single in 1964. He was hugely popular in those industrial cities of Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, all of which had huge populations of African-Americans who had migrated North from Alabama, Mississippi and other Southern states for jobs in the North. Alas in June 1948, Sonny Boy Williamson was killed in a robbery as he walked home from a gig in Chicago. Terrible news for the Williamsons, but as it turned out, very good news for Alex Miller of Mississippi.

Miller had been playing in those Southern states for several years billing himself as Sonny Boy Williamson to cash in, safe in the knowledge that the real Sonny Boy Williamson was way too busy in the North to ever play shows anywhere else. Once the real Sonny Boy Williamson was safely dead, Miller was free to start recording as Sonny Boy Williamson. With no explanation given, he simply picked up where the dead Sonny Boy had left off. Blues historians now differentiate them as SBWI and SBWII but at the time no one knew. He even moved up to Chicago from Mississippi in 1953 because there was so much work for him

When the Blues craze exploded over here in the late 1950s and early 1960s, he got on a plane and toured Europe and the UK and even appeared on top TV show Ready Steady Go! He obviously liked the place. A dapper man with money now in his pocket for once, he headed to Savile Row and had a two-tone suit tailored personally for him, along with bowler hat, matching umbrella, and an attaché case for his harmonicas. You can take the man out of Arkansas, but you can’t take Arkansas out of the man. On tour in the Midlands, he tried to cook himself a tasty bit of rabbit in a coffee percolator of all things and set his hotel room on fire.

He didn’t enjoy that sharp suit for long. He died on May 25, 1965 of an apparent heart attack suffered in his sleep the night before. He had adopted the real Sonny Boy Williamson’s birthday to complete the subterfuge, so everyone thought he was 65. Actually he was 52.

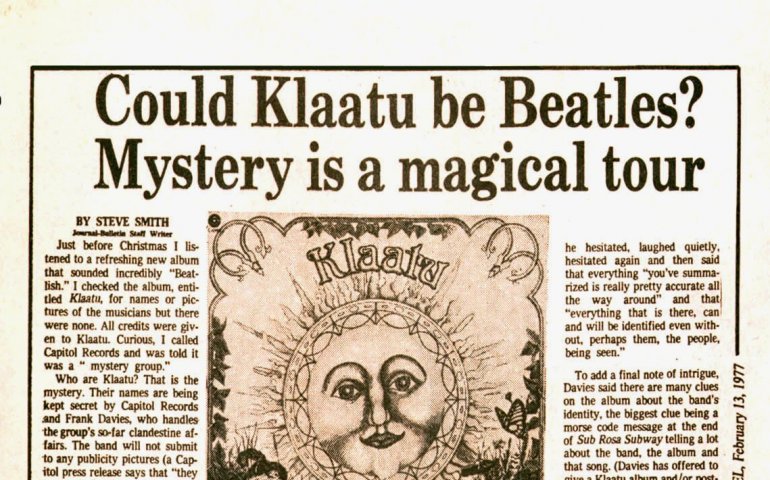

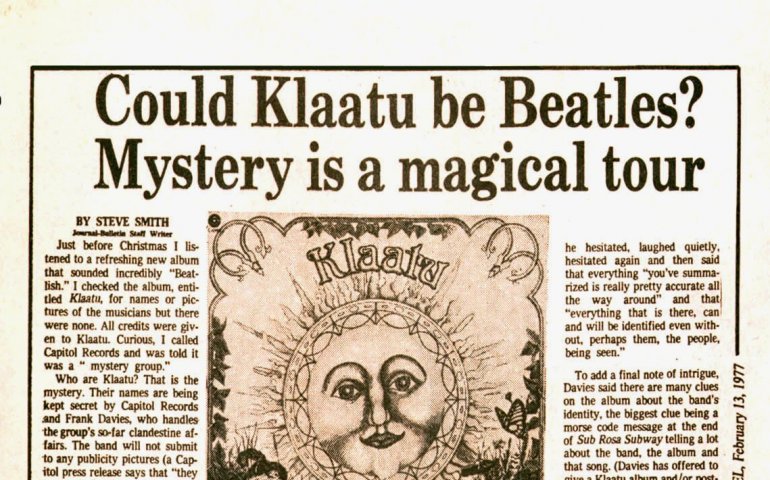

Could Klaatu Be Beatles? Mystery Is A Magical Tour

It’s 1976 and a band called Klaatu – Klaatu was the extraterrestrial in the 1950s sci-fi film The Day The Earth Stood Still – released an album called 3.47 EST. Oddly, mysteriously it had none of the usual information about the group, no photos, no songwriting credits, no contacts and it came out on Capitol Records (lest we forget the Beatles’ label in North America) . On top of that the sleeve of Ringo Starr’s latest album Goodnight Vienna had the drummer standing in the doorway of the spaceship from The Day The Earth Stood Still, dressed as Klaatu. The lead singer did rather sound like Beatle Paul and the guitars were a lot like George’s playing. There were even a few Yeah Yeah Yeahs in there too in case we didn’t get the message

One person who did get the message was Steven Smith of the Rhode Island Providence Journal, who reviewed the album with a story titled Could Klaatu Be Beatles? Mystery Is A Magical Tour’. he even contacted Capitol Records for more information but as sales had been a bit slow and figuring this might help sell a few albums, they refused to confirm or deny. He felt his only conclusion was to announce that this was an anonymous record by the Fab Four. Then all hell broke loose sales-wise.

AM and FM radio who loved the Beatles and whose listeners were desperate for the Fab Four to reform, began to play tracks from the album and other stations caught on to the story. Within weeks Klaatu were being played all across the US. It wasn’t just an American phenomenon. It was reported around the world, including the UK, although the New Musical Express famously squashed the rumours with an article under the title Deaf Idiot Journalist Starts Beatle Rumour. In the end some bright spark went to the US Copyright Office and discovered that the songs were copyrighted not to Lennon, McCartney, Harrison or Starkey, but to John Woloschuk, Dee Long and Terry Draper and Klaatu were actually a dull group of Prog Rockers from Toronto.

They made a number of albums, all apparently very good if you like that kind of thing, sold well in Canada but nowhere else now people knew they weren’t the Beatles. It was all 40 years and the only reason you’d remember them now is because they wrote the Carpenters Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft (The Recognized Anthem of World Contact Day).

The Fake Zombies

The Zombies were very nice lads from St Albans, who enjoyed a few hits here and in the USA as part of the British Invasion. By 1967 though, it was pretty much all over, despite them making they masterpiece Odessey & Oracle, so they packed it in and went their separate ways.

However a couple fo years later, a DJ in Michigan started playing a track from Odyssey & Oracle, a song called Time of the Season so it was re-released and stormed upon to Number 3 in the charts. There was all of a sudden demand for a Zombies tour but they were all off doing other things and weren’t interested. Luckily a dodgy promoter in Bay City, Michigan, Delta Promotions, was and did what anyone would do if they were trying to fake a 5-piece band from St Albans: they found a 4-piece blues band from Dallas, Texas, took some promo photos (two of them were wearing cowboy hats) and set them out on tour as The Zombies. If anyone asked where the keyboard player was, they had to say he’d been busted and was in jail.

They were terrible, which is not surprising as they were a blues band from Texas not a pop group from St Albans but there was no internet or social media so they just moved on to another town. Newspaper reviews mentioned bad sound, shoddy playing, and unimpressed audiences but by the time the paper came out the Fake Zombies were hundreds of miles away. They played small clubs in Michigan and Wisconsin and went up into Canada, where they appeared on TV and played a gig in a prison.

The promoters were getting away with it, so they decided they’d make twice as much money with a second group of Fake Zombies. The second fake Zombies were a five-piece and at least had a keyboard player. They were also very good. If you heard them play Time of the Season, you couldn’t really tell the difference. The real Zombies did find out and were furious but there wasn’t a lot they could do. In the end it was Rolling Stone magazine that broke the story in December 1969, titled The Zombies Are A Stiff.

Still Delta Promotions continued their dodgy business They had a fake version of The Animals and even a fake version of the Archies, which is bizarre because the Archies were a fake band to start with. It was also Delta’s downfall as the Archies were controlled by a very shrewd and powerful publisher and businessman called Don Kirshner, who had the clout – and the lawyers – to take Delta down, which they did. With Delta Promotions dissolved, the bands on the Delta roster headed back home. The Texas Zombies returned to Dallas where they ditched their Zombies past and returned to their normal lives. Tow of them, Dusty Hill and Frank Beard formed ZZ Top with guitarist and singer Billy Gibbons. They released their first album in 1970 and have since sold around 60 million albums worldwide.

Why Did You Do It? The fake Fleetwood Mac

Fast forward to 1974 and the lessons of Delta Promotions had obviously not been learnt. Fleetwood Mac had by this point been a blues band led by godlike guitar player Peter Green and were yet top be the radio-friendly AOR behemoth of Rumours led by Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham. In fact, they were in a bit of a rut, constantly on tour in the US where they retained some kind of audience. However the John and Christine McVie’s marriage was under strain, there was a lot of drinking and drugging and Mick Fleetwood knew that their new guitarist was having an affair with Mick’s wife. Not surprisingly they didn’t fancy slogging round America in a tour bus, so they cancelled any remaining dates to sort themselves out and have a nice break. However, they didn’t realise that they were contractually obliged to play and would be sued for huge amounts of money if they didn’t play them. The financial losses could be huge.

So rather than lose a fortune, their manager Clifford Davis recruited a British band called Legs and sent them out on tour as a Fake Fleetwood Mac. They were told that Mick Fleetwood would join them on later dates, but when he didn’t show up, the excuse was he’d just dropped out when he rumbled the scam. Which audiences soon did too, what with there being absolutely no actual members of Fleetwood Mac on stage at any time. After a dreadful review in Rolling Stone, the tour ground to a halt as the news spread and promoters cancelled dates, although when they had played they had gone over a bit of a storm apparently. Then it all went legal. Everyone sued each other and they couldn’t work for months and months. Most of the industry assumed they were finished, although the real Fleetwood Mac relocated permanently to LA, recruited Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks at a studio in LA and have sold well over 100 million albums since

As a postscript, the musicians in the fake Fleetwood Mac later formed Stretch, who had a huge hit with Why Did You Do It? which is allegedly about Mick Fleetwood.

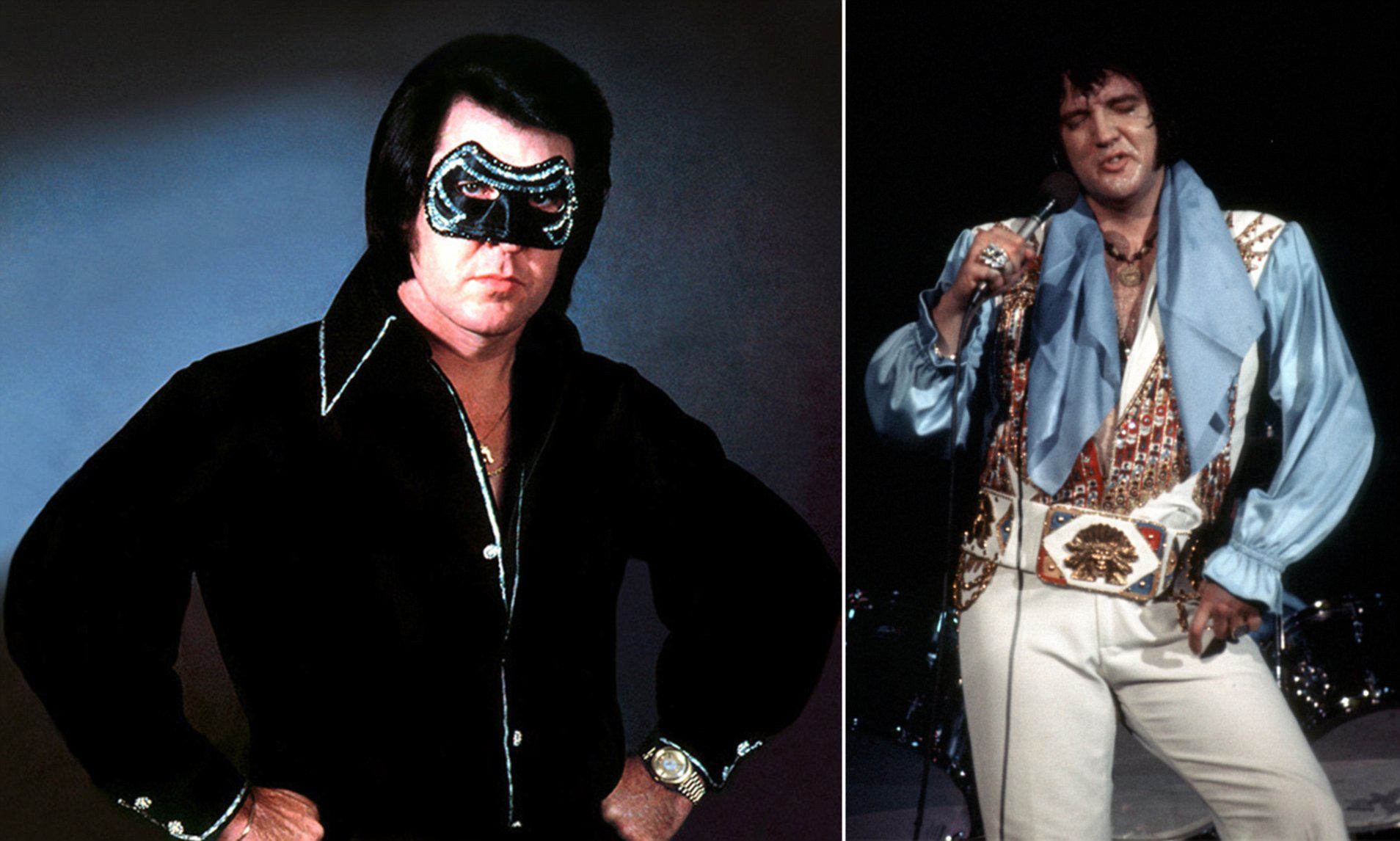

Orion: the Man who would be King

Elvis Presley of course died in Memphis in August 1977 of a heart attack after years of prescription drug addiction and dreadful diet.

Or did he? Many think he’s still alive. The first alleged sighting of a non-dead King of Rock’n’Roll was two days after Elvis’ death, when a bloke at Memphis airport bought a one-way ticket to Buenos Aires, Argentina. Apparently he looked a bit like Elvis and used the name Jon Burrows, which was an alias of Elvis had often used when booking hotels for himself. Some swear he’s in the 1990 movie Home Alone as the bearded man behind Kevin’s mum as she checks in at the airport to fly home from Paris. Last year, when a man with a white beard was spotted visiting Graceland, fans were convinced it was Elvis.

The appetite to want Elvis not to be dead is huge and has been since 1977. At the end of that year, a cash-in pulp fiction novel called Orion was published. It was the story of a hugely successful Southern rock star called Orion Darnell who fakes his own death to get out of the rat race and live a normal life. In case you missed the link, the publishers cheekily added the words Is Elvis Really Dead? on the cover. It flew out of the stores and up the best seller lists.

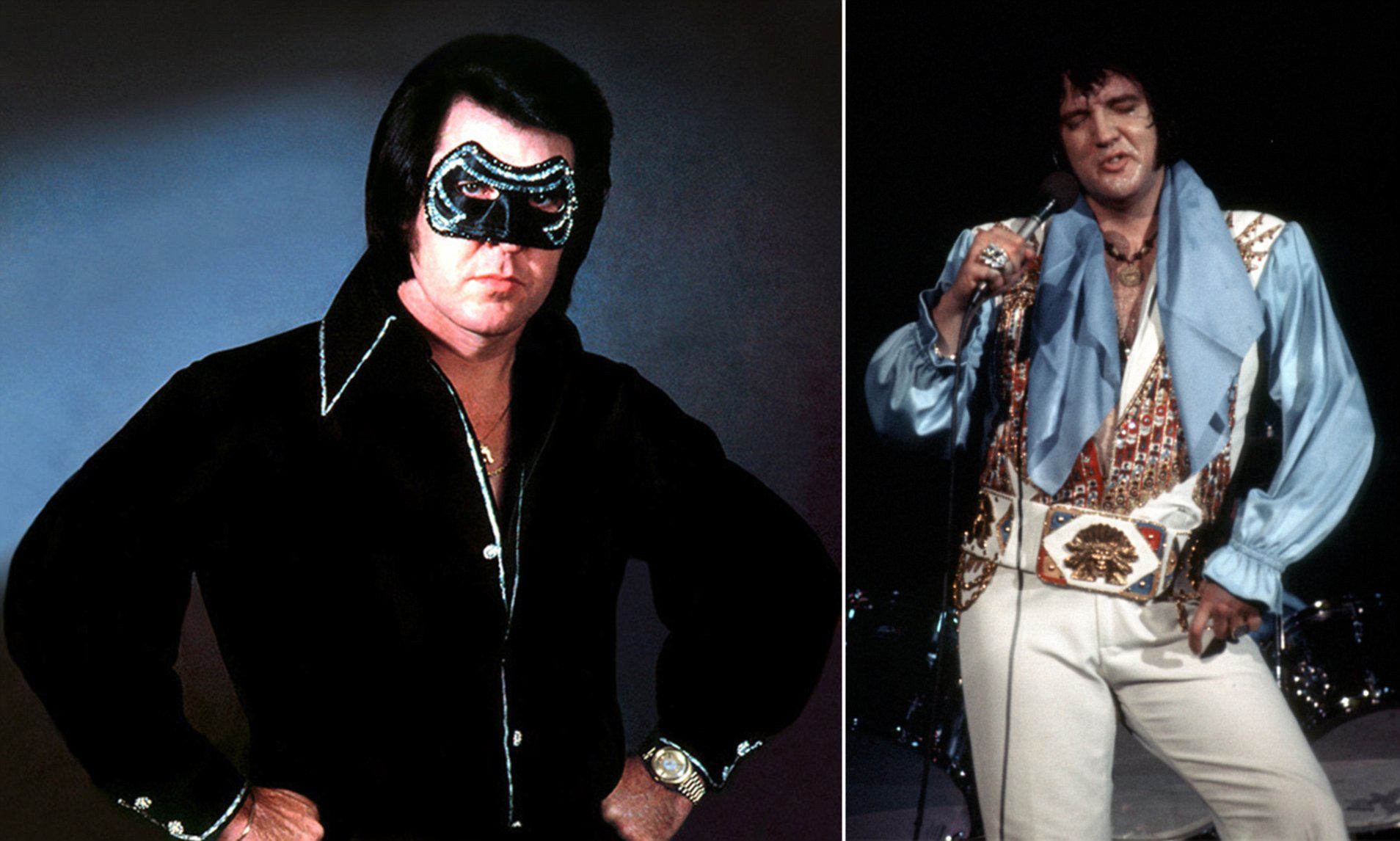

A few weeks later, Sun Records, the label that first released his music, put out an album of duets between Jerry Lee Lewis and a singer who sounded uncannily like Elvis. Not a little like Elvis, like Les Grey of Mud or Shakin Stevens, but uncannily, preternaturally like Elvis. To ride the coat tails of the Orion bestseller, Sun Records called him Orion and had him wear a mask, which he never took off. To be honest he didn’t look unlike Elvis. He had quite a luxurious black Barnet, liked a gaudy jump suit like the King himself and there was that voice.

There was frenzied speculation that these were new unreleased Elvis tracks and keen to have them sell, Sun were happy to create the mystique that it was Elvis. No one at Sun said it wasn’t Elvis. Sun’s first Orion album was called Reborn and people desperate for Elvis to still be among us bought it in large numbers. He sold out large theatres, always in the mask and always sounding uncannily like Elvis. He had massive following, released 9 albums between 1978 and 1982, some country, some gospel, some rock and roll, but all Elvis. There were 20,000 in his fan club and they all just really wanted it to be Elvis. They argued he wore a mask because he’d had plastic surgery to disguise himself after he died, although no one questioned why the biggest rock and roll singer would come back, er, as a rock and roll singer. When people started saying hang on he doesn’t actually look like Elvis, his manager started the rumour that whilst he might not look exactly like Elvis, he did look the spitting image of Vernon Presley, Elvis’ dad, so you know he might be his brother.

There was frenzied speculation that these were new unreleased Elvis tracks and keen to have them sell, Sun were happy to create the mystique that it was Elvis. No one at Sun said it wasn’t Elvis. Sun’s first Orion album was called Reborn and people desperate for Elvis to still be among us bought it in large numbers. He sold out large theatres, always in the mask and always sounding uncannily like Elvis. He had massive following, released 9 albums between 1978 and 1982, some country, some gospel, some rock and roll, but all Elvis. There were 20,000 in his fan club and they all just really wanted it to be Elvis. They argued he wore a mask because he’d had plastic surgery to disguise himself after he died, although no one questioned why the biggest rock and roll singer would come back, er, as a rock and roll singer. When people started saying hang on he doesn’t actually look like Elvis, his manager started the rumour that whilst he might not look exactly like Elvis, he did look the spitting image of Vernon Presley, Elvis’ dad, so you know he might be his brother.

Was he Elvis? No, he was 34-year-old Jimmy Ellis from Orrville AL whoa been singing exactly like Elvis Presley since high school. He had had a singularly unsuccessful recording career in the 1960s but no one wanted another Elvis, there already was one. So he went back to the family business, which happened to be training horses. His heart though was always in music so one day in 1975 aged 30, he quit, sold everything he had and went to California to get into the music business. He hired a manager, a choreographer and a stylist to launch his career. But there was already one Elvis, so how do you market another.With difficulty and no success as it happens. After a year, his money ran out and it was back to the horses, with a sideline as an Elvis impersonator.

Then in August 1977, Elvis died.

Sun Records – now run by the less-than-scrupulous Nashville hustler Shelby Singleton – still owned the masters to Elvis’ early songs as well as those of Jerry Lee, Charlie Rich and Carl Perkins. With Elvis dead and the market going nuts for anything Elvis-related he overdubbed Jimmy EIllis’ voice onto all sorts of old Sun recordings and released them. The Orion best-seller gave Singleton an idea. He got Ellis to change his name to Orion and go out on the road. Ellis, after 20 years as a failed singer, thought this might be his shot. He even agreed to wear the mask, he so desperately wanted to be a successful singer.

He was the masked singer for five years, criss-crossing the USA and even touring the UK and Europe but still thought this might be a means to an end and that one day the mask might come off and Jimmy Ellis might be the big star. Alas it was not to be and when his manager finally told him that he was never going to be successful without the mask, he tore it off his face on stage one night and threw it into the audience. It ended his career. No one wanted him, they wanted the guy who sounded just like Elvis.

He didn’t stop singing trying a whole load of different stage names but after 5 or 6 years, skint and over 40 he found a new mask and was Orion once again. He barely made a living so had to do other jobs to support himself and his family. He went back to the family farm and then opened a Pawn Shop in his hometown of Orrville AL with his ex-wife. In December 1998, they were both killed in an armed robbery at the shop. The robber couldn’t get the till open and so ran out with no cash, having killed 2 people for nothing. Nothing at all.

Milli Vanilli: Girl You Know Actually It Isn’t True

Milli Vanilli, two ridiculously good looking blokes in very tight trousers who sold several million records in 1989 and 1990, especially in America where they had three Number One singles, videos in permanent rotation on MTV and a Grammy for Best New Artist. The only problem was they didn’t actually sing on their records

They were formed in Munich by a German singer, songwriter and producer called Frank Farian, formerly an unsuccessful pop singer who had form for this kind of thing. In 1975, he came up with a song called Do You Wanna Bump? in fact a dangerously funky version of Prince Buster’s Al Capone with Farian’s tuneless and heavily accented voice over the top. He needed some good looking people to sell it so he recruited a proper female singer, a couple of exotic models and a whirling dervish of a dancer who couldn’t carry a tune in a bucket. They were called Boney M.

Boney M records sold 80 million copies throughout the rest of the 1970s, particularly here in the UK where they had a dozen Top Ten hits and albums that sold in the millions. People like me often look back on pop records of that time which I disregarded because I was listening to the Pistols and think actually that’s quite a good pop record. But with Boney M you really can’t. They are irredeemably terrible.

Fast forward to 1988 and Frank Farian is at it again. He had finished all the songs using session singers but needed someone to front it. He found two guys in a disco in Munich who were the best dancers there: Fabrice Morven who was French and originally from Guadeloupe; and Rob Pilatus, who was German, the son of an exotic dancer and American GI. He called them Milli Vanilli, claiming it was Turkish for Positive Energy (it isn’t, it’s the name of an old disco in Berlin).

Their debut album, known in the USA as Girl You Know It’s True, was released in late 1988 and had sold 10 million copies worldwide in a few months, mainly due to irritatingly catchy songs and sexy videos featuring Rob & Fab in phenomenally tight shorts. MTV invited them to tour America and they spent the Summer lip-synching their way across the country until one fateful night in Bristol, Connecticut when the tap e got stuck, repeating the line Girl you know it’s true over and over. They pretended to sing on for a while but just then ran off stage with the tape still playing their voices. Even then, the crowd didn’t seem to care, but suspicions were raised.

However their biggest problem was when they won the Grammy Award for Best New Artist. Grammys are serious awards and the press decided that a little more scrutiny might be in order. One or two newspapers had heard about the incident with the tape and started looking into them. They couldn’t work out why the vocals on their records had such strong authentic American accents, yet when they had interviewed Rob & Fab they could barely speak English and had impenetrable German accents. Their enquiries were helped when the actual singers on the record suddenly revealed by press release that Rob & Fab were imposters and hadn’t sung a note. Farian buried the story by paying them handsomely to retract what they had said and got away with it. But worse was to come.

Emboldened by all the success, Rob & Fab actually demanded to sing on the next album. Farian, a wily music biz player, knew that would be a disaster, so he who blew the gaff himself with a news conference in November 1990, where he announced that Rob & Fab had mimed the whole thing and had not sung a single note on their records. Arista Records dropped them immediately and deleted their album. Their Grammy was revoked, the first time that had happened and they had to send it back

It didn’t end there. Twenty-two class-action law suits were filed in the US, charging that Arista Records had perpetrated consumer fraud by implying that Rob and Fab had sing on their own records. The plaintiffs, groups of fans, cited the “emotional distress” they experienced when the truth was revealed. They are demanded reimbursement of the money they spent on Milli Vanilli records, concert tickets and merchandise, as well as legal fees and costs. Arista were told to offer refunds to the tune of $1 if you bought a single, $2 if you bought an album or cassette, $3 if you bought a CD or video and $2.50 for a concert.

The actual singers released an album credited to The Real Milli Vanilli in 1991, which flopped. Rob & Fab tried a comeback but their album Rob & Fab sold around 2000 copies. Amazingly in 1997 they made another album with Frank Farian where they sang but Rob Pilatus who had not handled the scandal well, slid into substance abuse, attempted suicide and was arrested several times. Despite 10 stints in rehab, Pilatus couldn’t kick his habits. He died aged 32 after an overdose just as it was about to come out so it remains unreleased.

Paul is Dead

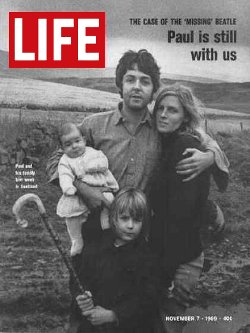

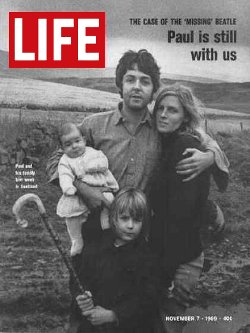

Possibly the most famous hoax of all. In November 1969, the world went crazy with the rumour that Paul McCartney had died.

The story was this: Paul McCartney had attended an all-night recording session at Abbey Road NW8 on Wednesday, November 9, 1966 but had had a furious row with the other Beatles and had stormed out of the studio into his car. He then picked up a female hitchhiker on his way to a friend’s house but the woman became so excited when she realized who had picked her up that she threw her arms around Paul and caused him to lose control of the car. Both Paul and his passenger were killed when the car swerved off the road and hit a stone fence.

Furthermore, not wanting to lose potential record sales, the Beatles’ record company suppressed the story of Paul’s death and brought in a lookalike to replace him, a man named William Campbell, who was an actor and who had won a Paul McCartney lookalike contest. With a little plastic surgery, William Campbell had taken Paul’s place in photos of the group. The surgery had been successful except for a small scar above his lip. And, by an extraordinary stroke of luck, he could also sing and just happened to be a songwriter with an exceptional ear for pop melodies.

Ss if that weren’t far fetched enough, the surviving Beatles agreed to go along with this scheme, but as a protest decided to deliberately leave clues on their subsequent albums about Paul’s death and the imposter who took his place.

The Beatles had just released Abbey Road, where the cover of the 4 of them walking over the zebra crossing symbolises a funeral procession. Lennon, dressed in white, symbolises the preacher or heavenly figure. Ringo, dressed in black, is the undertaker or mourner. George, in denim jeans and shirt, symbolises the gravedigger and McCartney, barefoot and out of step with other members of the band, symbolises the corpse. In some cultures there is the custom to bury people without their shoes apparently. He’s also holding a fag in his right hand – although at that point was probably the most famous left-handed person in the whole world! The VW Beetle in the background with the number plate LMW 28IF, the age Paul would have been (actually he would have been 27)

And they were the most sensible, reasonable ones. Fans also went back through past albums and came up with all manner of bizarre stuff, like how on the Sergeant Pepper cover, if you put a mirror half way up the drum skin that says LONELY HEARTS you get I ONE IX arrow Die – the arrow points up to McCartney – IX being 9 in Roman numerals and (of course) McCartney has 9 letters. QED.

What about their greatest hits set, A Collection of Beatles Oldies– the letters O and L in Oldies are of course the letters immediately before P & M in the alphabet so it could therefore read PM DIES – in the same way people think the computer in 2001 HAL is IBM shifted by one letter. If you play the Strawberry Fields Forever single backwards, there are messages in the final section that say I buried Paul (although it actually sound more like cranberry sauce.)

All a load of old tosh of course and here’s how it started. On 17 September 1969, the student newspaper of Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa published an article titled Is Beatle Paul McCartney Dead? based on a rumour they’d heard from stoned students from California that clues to McCartney’s death could be found among the lyrics and artwork of the Beatles’ recordings. One suspects student mischief and some exotic smoking might have been involved.

The Drake University story was picked up by the University of Illinois’ student newspaper, as well as other college newspapers in that part of the country. Then a copy found its way to Detroit radio station WKNR FM on 12 October where DJ Russ Gibb hosted a call in show about the rumour for the next hour, with the effect that hundreds of hysterical fans calling in to see if it was true.

Two days later the story appeared in the University of Michigan’s newspaper, with a lot more completely made up detail. They created the identity of Paul’s replacement, William Campbell, inserted new invented clues from their new album Abbey Road. The author assumed everyone would think it as a spoof and was then astonished when the story was picked up by proper mainstream newspapers across the United States, like, the Des Moines Register, the Chicago Sun Times the Washington Post, New York Times, the LA Times and The Times in London in pretty quick succession. This was the old world’s version of going viral.

In fact, the rumour though had become so widespread that both the BBC and Life magazine sent reporters to Paul’s farm in Scotland and get photos. Paul had taken refuge from the Beatles’ legal battles and he was not at all happy to be confronted by reporters but agreed to let an interview with Life, which did calm everybody down a bit. There was an upside though. In November 1969, Capitol Records sales managers reported a significant increase in sales of Beatles catalogue albums, attributed directly to the rumour. It was all student mischief that went round the world.

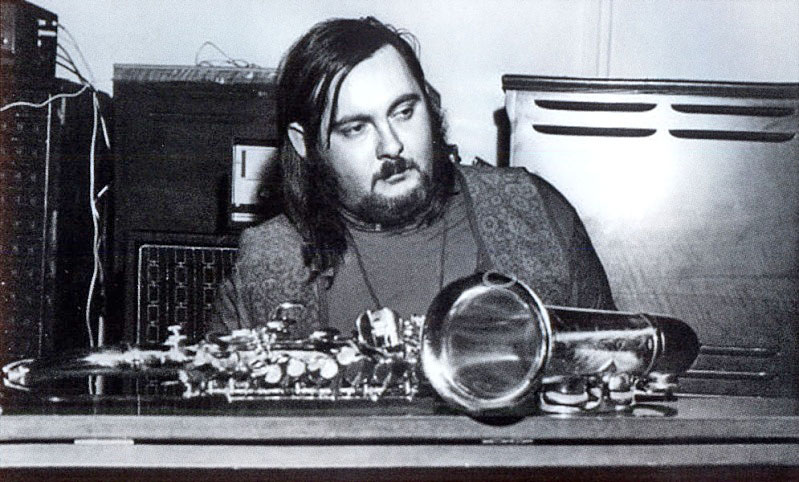

But they never were going to make it. They didn’t look the part, as amazing as the music was. Graham Bond was a huge fat guy, Dick Heckstall-Smith was balding with glasses, Ginger, as someone put it, looked like he would eat your loved ones. Only Jack Bruce was a half decent looking guy and if your competition is someone like the Moody Blues, five good looking chaps from Birmingham in fashionable smart suits, you’re going to struggle. The whole of the British Invasion passed them by. What an opportunity lost!

But they never were going to make it. They didn’t look the part, as amazing as the music was. Graham Bond was a huge fat guy, Dick Heckstall-Smith was balding with glasses, Ginger, as someone put it, looked like he would eat your loved ones. Only Jack Bruce was a half decent looking guy and if your competition is someone like the Moody Blues, five good looking chaps from Birmingham in fashionable smart suits, you’re going to struggle. The whole of the British Invasion passed them by. What an opportunity lost!

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-5369804-1391717398-1977.jpeg.jpg)

There was frenzied speculation that these were new unreleased Elvis tracks and keen to have them sell, Sun were happy to create the mystique that it was Elvis. No one at Sun said it wasn’t Elvis

There was frenzied speculation that these were new unreleased Elvis tracks and keen to have them sell, Sun were happy to create the mystique that it was Elvis. No one at Sun said it wasn’t Elvis